When we use a space, we gain first-hand insights into how well it supports our thoughts, feelings and behaviors. Such collective experiences can be assessed and understood using survey-based post occupancy evaluations (POEs), a method that has been shown to be effective, efficient and affordable. Historically, these surveys focus on comfort and satisfaction with specific characteristics of an environment — for example, lighting or acoustics. However, our relationships with our environments are complex. Spaces have the potential to impact both our mental and physical health, the daily goals we set for ourselves, and even the ways we form and maintain relationships with others and organizations.

Both industry professionals and scientists have spent time digging into these complex relationships, and in recent years the focus has shifted towards the ways in which environments support or hinder occupant health and wellbeing. As a result, these inquiries have shown us that while aspects of comfort and satisfaction with indoor environmental quality are certainly important in assessing building performance, they are not the only — or even most important — factors we should be focused on when trying to create and maintain successful spaces for people. With this understanding, a question also emerges: are our POE surveys measuring all the factors we need them to?

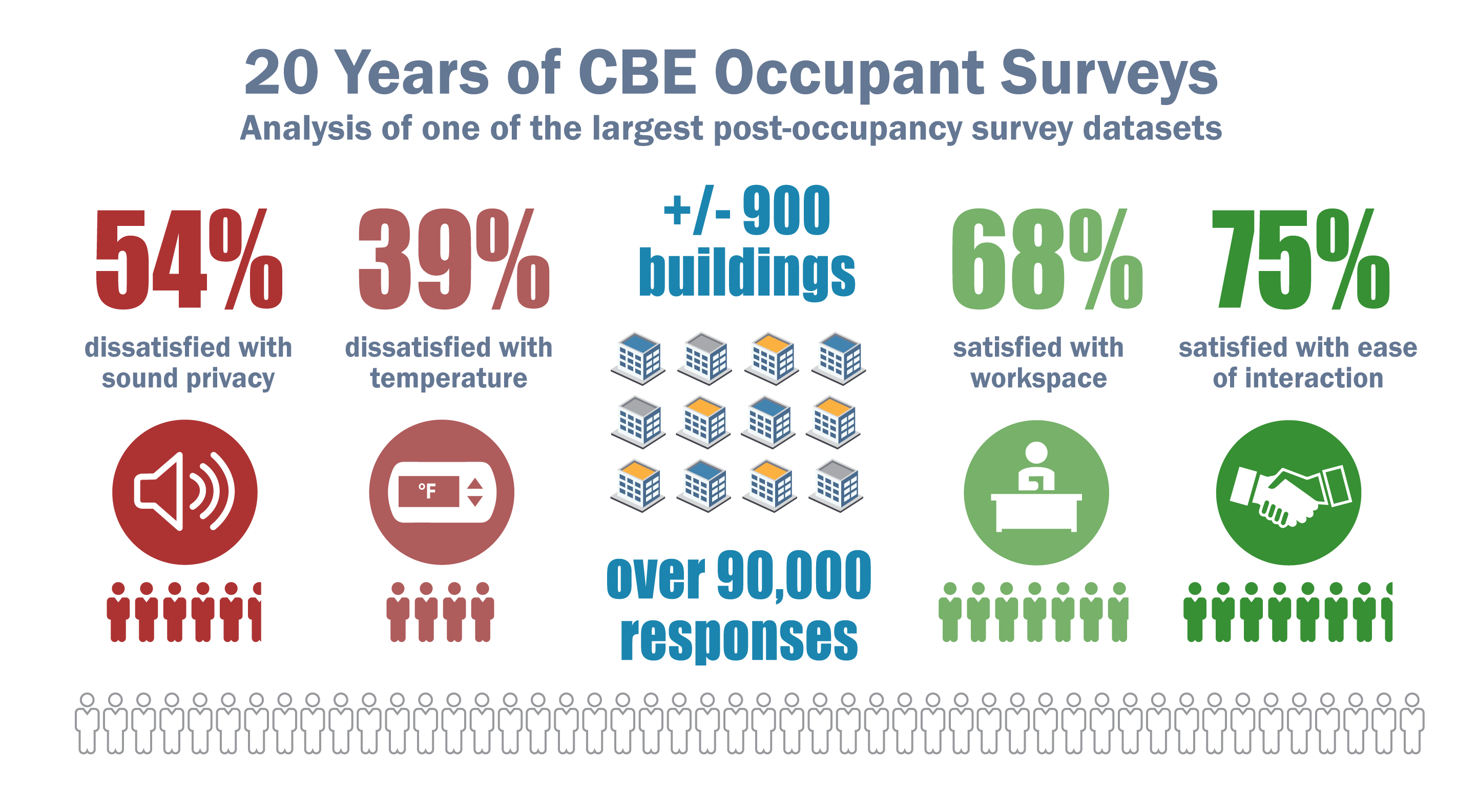

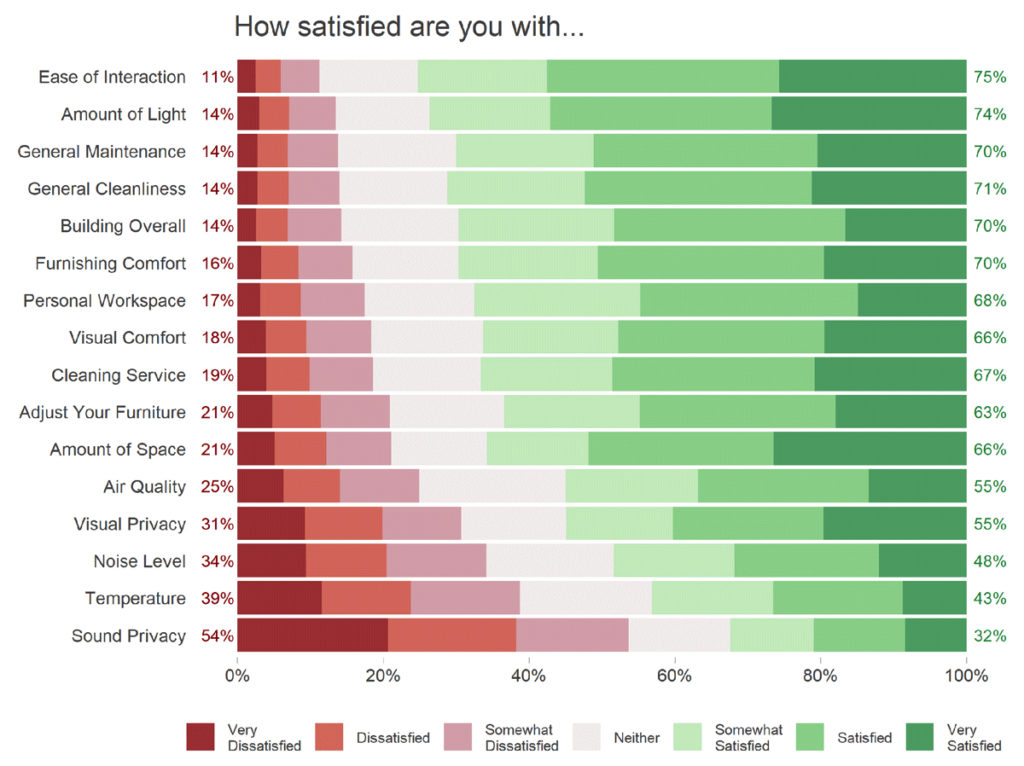

As any good journey towards change begins, we started by looking inward. Over the past 20 years at the Center for the Built Environment, we have created and maintained one of the most widely used web-based POE surveys on the market: the CBE Occupant Survey. The survey is frequently used to achieve building certification (for standards such as LEED and WELL) and/or to evaluate a building’s performance and compare it to the tool’s benchmarking metrics. Over these two decades, the survey has been used to construct an extensive database of over 90,000 respondents from over 900 buildings. This allowed us the unique opportunity to scientifically evaluate the measurement and benchmarking properties of our tool, as well as summarize the characteristics of the database to date. For example, we found that 68% of the survey respondents are satisfied with their workspace, as shown in the chart below. Satisfaction is highest with respect to characteristics such as the ease of interaction, the amount of light, and cleanliness. Conversely, the survey results show that dissatisfaction is highest with sound privacy, temperature, and noise level. You can read more details of our statistical assessment of the tool and our summary of the database in our Buildings and Cities paper.

In doing this work, we were also able to identify new directions for future POE survey advancement. As a field, we have already begun looking beyond creating spaces that are just satisfactory, but rather those that help people thrive. Therefore, it’s time we start looking beyond just measuring occupant satisfaction to determine building success. We should also incorporate measures that gauge how spaces impact occupant health and wellbeing. We can extend our work to assess other complex factors such as whether or not spaces support the cognitive and emotional needs of its occupants, or even more simply, how a space is functioning and utilized by its inhabitants. We should also explore more about the occupants themselves, because as we learn more about the people in a space, we then also have the potential to unlock why they may be using that space or perceiving it in the ways they are — and that insight is key to supporting quality design that withstands the test of time. Incorporating measures such as occupant personality, need for control or personalization, job satisfaction and commitment could be steps towards this goal. Furthermore, we see a need for more standardized measurement across the board: first within the field of building science with POE surveys like ours, but also in the incorporation of new metrics. Many fields within the social and biological sciences (such as psychology, public health, and medicine) have developed a wide range of reliable and valid survey instruments that could be used to measure factors known to be important in built spaces— such as occupant stress, wellbeing, personality, and health. We encourage POE developers and users to research these metrics and see how they could be incorporated into the tools they create and use.

Any good psychometrician would tell you even the most well-designed surveys have their limits. At CBE we are strong advocates for the use of multiple methods when addressing any question. By utilizing multiple methodologies, we are able to explore a challenge from multiple vantage points, and hopefully begin to overcome some of the shortcomings of one methodology with the use of another. With the many advancements in technology today, we are at a point in time where the way we conduct POE surveys can rapidly expand and be reimagined. We have the ability now to provide occupants with shorter, targeted surveys that can be delivered in a variety ways (e.g., via smartwatch, text, email, kiosk). We should begin exploring when, and with which assessed factors, we can create shorter, in-the-moment targeted surveys to gain greater insight compared to those larger surveys aimed at global experiences (such as the CBE Occupant Survey). Environmental sensors, both fixed and wearable, offer a wealth of knowledge about the way a space is being used and performing without interrupting the daily life of occupants. By synchronizing technology in tandem with POE surveys (both global and shortened) we have the power to provide environmental context, and thus, deeper understanding of the self-reported perceptions put forth by occupants completing a survey. (For instance, we recently did this for thermal comfort and the results are promising.) These are a just a few examples, but as technology continues to improve we can more creatively and effectively measure design success and the occupant-space relationship.

As we stated, our journey towards invoking POE change began with self-inquiry. But this type of reflection becomes most useful when it is followed by directed action; as Ghandi said, “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” To this end, using our critical analysis of our work, we’re taking tangible steps with our own occupant survey tool to make these shifts. We have determined places in which the questions our tool asks can be reduced, thus allowing space for new factors we wish to measure (such as wellbeing, personality, stress, need for control, and job satisfaction). This reduction has also allowed us to recalibrate our benchmarking metrics and will allow us to grow a new database and benchmarks on these incorporated variables. We have also shifted our scale so that it is more user friendly and in alignment with standard psychometric practices. We have also recently developed a new survey tool specifically aimed at achieving WELL certification — which requires users to assess many of the factors we know contribute to a successful occupant-environment relationship. Finally, we now offer a more detailed and visually inviting report format to help our users to better understand their survey results.

These are just a few of the recent and upcoming enhancements to the CBE Occupant Survey. We’re really excited to be advancing this resource, and we are energized and hopeful about the potential for future advancements of POEs and their ability to support our shared goal with you — to craft and maintain spaces that truly support those who use them. We invite you to learn more about how you can use the CBE Occupant Survey in your next project.

Reference: Graham, L. T., Parkinson, T., & Schiavon, S. (2021). Lessons learned from 20 years of CBE’s occupant surveys. Buildings and Cities, 2(1), pp. 166–184. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5334/bc.76